Are you struggling to understand how children think at different ages? Wondering how to tailor your classroom or preschool environment to match their learning level? Feeling unsure about which teaching strategies truly align with how kids develop mentally?

Piaget stages of development provide a clear framework for understanding how children’s thinking evolves from infancy to adolescence. This framework allows educators and school planners to align teaching methods, classroom design, and educational goals with children’s actual cognitive abilities at each stage. It’s a crucial tool for anyone involved in early childhood education who wants to foster deeper engagement, stronger problem-solving skills, and age-appropriate learning outcomes.

Jean Piaget’s theory is not just academic—it’s practical. From choosing the right preschool furniture to designing lesson plans, understanding Piaget stages helps us create environments where children naturally thrive. In this guide, I’ll walk you through each stage, its characteristics, and how to use this insight to improve educational outcomes and early learning environments.

1. Who Was Jean Piaget and Why His Stages Matter

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was a Swiss psychologist best known for his groundbreaking work in child development. Originally trained in biology and philosophy, Piaget brought a scientific lens to the study of how children acquire knowledge. His central insight—that children are not just “less competent” adults but thinkers who progress through qualitatively different stages of cognitive development—revolutionized developmental psychology and education theory.

His work led to what we now call the “Piaget stages,” a framework that outlines how children’s cognitive abilities evolve in clear, progressive steps. This concept shifted the educational landscape from a one-size-fits-all approach to one that respects the developmental readiness of each child. Rather than pushing abstract thinking too early, Piaget’s theory teaches us to match tasks and environments to a child’s current mental capabilities.

Why is this important? Because understanding Piaget stages is the key to aligning educational materials, teaching methods, and even classroom layouts with the way children actually think and learn. For example, a child in the preoperational stage (typically ages 2–7) benefits from visual aids and concrete play-based learning, while a child in the formal operational stage (12 and up) can begin tackling abstract reasoning and hypothetical problems.

In preschool and early education settings, this knowledge is essential. It can help educators decide when to introduce specific activities, how to structure the classroom, and which types of furniture—like play kitchens, manipulatives, or sensory tables—are developmentally suitable. Piaget’s stages don’t just inform what children learn; they influence how they learn and how we support them.

Understanding Piaget isn’t just for psychologists—it’s for anyone serious about quality childhood education. As we explore each of the Piaget stages in this guide, you’ll begin to see how deeply these ideas connect to practical decisions in the classroom, especially when it comes to planning learning environments that truly nurture a child’s growing mind.

2. Overview of Piaget Stages of Cognitive Development

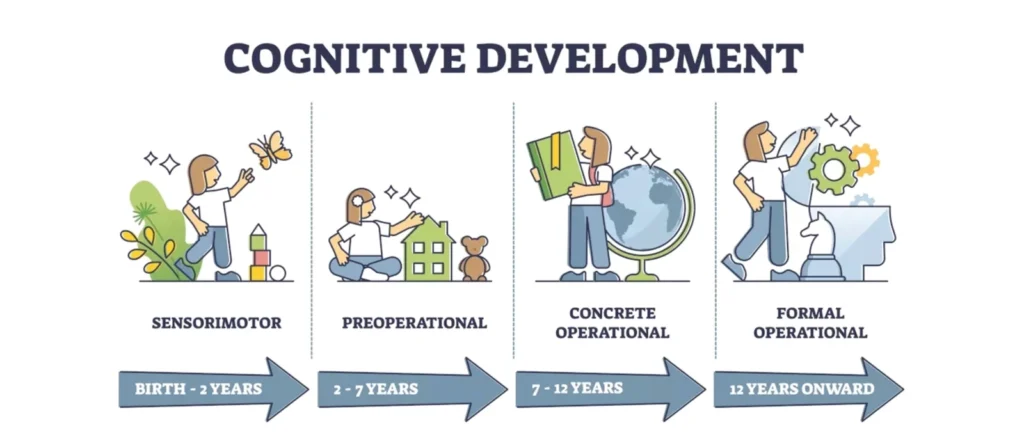

The Piaget stages of development outline a child’s cognitive journey from reflexive, sensory responses to abstract, logical thought. Piaget proposed that children do not simply accumulate knowledge, but rather, actively construct understanding in ways unique to their developmental stage. This theory consists of four universal stages, each marking a qualitative shift in cognitive ability:

- Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 years)

Children learn through sensory experience and movement. They explore the world using touch, sight, sound, and action. A key milestone here is the development of object permanence—the realization that things still exist even when not seen. - Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 years)

In this stage, children begin to use symbols, like words and images, to represent objects. While they become more imaginative and improve their language skills, they also show egocentric thinking—struggling to see things from others’ perspectives. - Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 years)

Logical reasoning emerges, especially when dealing with tangible objects. Children in this stage can understand concepts like conservation, classification, and cause-effect relationships. They can also follow multi-step instructions and perform basic operations like sorting and measuring. - Formal Operational Stage (12 years and up)

Children can now think abstractly, reason hypothetically, and engage in systematic planning. This stage allows adolescents to form complex arguments, test hypotheses, and imagine possibilities beyond the present.

Each of these Piaget stages serves as a blueprint for understanding what kind of learning environment and materials are appropriate. Importantly, progression through these stages is sequential—children cannot skip a stage—and each builds on the competencies of the previous one. That’s why forcing a child into tasks beyond their cognitive readiness often results in confusion or frustration.

Understanding the overview of these stages equips educators, school administrators, and even furniture manufacturers with powerful insight. Whether you’re designing a kindergarten classroom or planning a curriculum, using the Piaget stages as your foundation ensures that you’re working with the child’s development—not against it.

3. The Core Cognitive Concepts Behind Piaget’s Stages

To fully appreciate the Piaget stages, it’s essential to understand the core cognitive processes that drive them. Piaget didn’t just list stages; he described the mechanisms by which children advance through those stages. These mechanisms are the building blocks of intellectual development, and they apply universally, regardless of culture or background. They include mental schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibrium.

3.1 Mental Schemas: How Children Build Knowledge

Schemas are cognitive frameworks or “mental structures” that help children organize and interpret information. From infancy, children begin creating schemas—like grasping, sucking, or recognizing familiar faces. These early schemas are based on sensory and motor interactions, but they evolve to include complex ideas as the child grows. For example, a toddler’s schema for “dog” might initially include only the family pet. As they encounter more dogs, the schema expands.

3.2 Assimilation: Fitting New Information into Existing Ideas

Assimilation occurs when a child incorporates new information into an existing schema. If a toddler who has a schema for “dog” sees a cow for the first time and calls it a dog, that’s assimilation in action. It shows how children try to make sense of the world using what they already know—even when their understanding is incomplete. This is an essential step in learning, as it drives curiosity and exploration.

3.3 Accommodation: Adjusting Ideas to Match New Information

Accommodation is the process of modifying an existing schema—or creating a new one—to fit new information. When that same child realizes that a cow is not a dog, they adjust their schema to differentiate the two animals. Accommodation reflects a higher level of cognitive flexibility and represents a step toward deeper understanding.

3.4 Cognitive Equilibrium: Balancing Learning and Understanding

Equilibrium is the mental balance between assimilation and accommodation. Children strive for equilibrium, and when they encounter something that doesn’t fit their current understanding (disequilibrium), they’re motivated to learn and restore balance. This dynamic process is what propels children through the Piaget stages.

By understanding these core concepts, educators can better guide children through cognitive challenges. These principles also help explain why developmentally appropriate activities—such as puzzles, role play, and open-ended problem-solving—are so effective in early learning environments.

4. The Sensorimotor Stage: Cognitive Beginnings (Birth to Age 2)

The sensorimotor stage marks the foundation of all cognitive development. According to Piaget, this is when infants begin to make sense of the world through sensory experiences and motor activities. From birth to about 24 months, babies transition from simple reflex actions to purposeful behavior. Everything they learn comes from interacting directly with the physical environment—touching, tasting, seeing, and moving.

This stage is typically divided into six substages, each showcasing progressive mastery of actions and mental representations:

- Reflexive Schemes (0–1 month): Newborns use inborn reflexes like sucking and grasping. Their interactions are reactive, not intentional.

- Primary Circular Reactions (1–4 months): Infants discover actions involving their own bodies, such as thumb-sucking, and repeat them for pleasure.

- Secondary Circular Reactions (4–8 months): Babies begin interacting with the environment—shaking a rattle or smiling at a face.

- Coordination of Reactions (8–12 months): Intentional behavior emerges. Infants can combine learned behaviors to achieve goals, such as pushing a block to reach a toy.

- Tertiary Circular Reactions (12–18 months): Experimentation begins. Babies deliberately vary their actions to see results (e.g., dropping objects to observe the response).

- Early Representational Thought (18–24 months): Mental representation forms. This is when object permanence fully develops—the understanding that objects exist even when not in sight.

Understanding this stage helps educators and caregivers provide environments rich in sensory exploration and safe motor activity. Soft mats, sensory bins, and toys with cause-and-effect features are ideal. This is also the time to introduce simple furniture like low open shelves and mobile learning stations, helping infants build spatial and physical awareness.

For furniture designers and early learning providers, such as those of us at XIHA Furniture, knowing the sensorimotor needs of infants is vital. Products for this age should prioritize safety, tactile engagement, and freedom of movement. Tables should be low and rounded; chairs should be soft and easy to grip.

The sensorimotor stage lays the groundwork for all future learning. Children at this age are not just playing—they are actively constructing the building blocks of thought.

5. The Preoperational Stage: Symbolic Exploration (Ages 2 to 7)

The preoperational stage is the second of the four Piaget stages of development, typically spanning from ages 2 to 7. During this critical time, children’s brains make tremendous leaps in symbolic thinking, language development, and pretend play. Unlike the sensorimotor stage—where learning is grounded in physical interaction—the preoperational stage allows children to start using mental imagery, symbols, and imagination to understand their world.

A hallmark of this stage is the rapid expansion of vocabulary and the use of language to express ideas. Children begin asking “why” questions, narrating stories, and engaging in complex pretend play. For example, a stick may become a sword, or a cardboard box might transform into a spaceship. These symbolic representations are not just cute—they’re fundamental to how children in this Piaget stage build abstract thinking.

However, cognitive limitations also characterize the preoperational stage. Children often exhibit egocentrism, meaning they struggle to see situations from others’ perspectives. This is best illustrated by the classic “Three Mountains Task,” where a child assumes others see exactly what they see. They also grapple with centration—focusing on one aspect of a situation while ignoring others—and struggle with conservation, the understanding that quantity remains constant despite changes in shape or appearance.

Understanding these features helps educators and parents align activities and materials with cognitive readiness. Teaching should be concrete, visual, and interactive. For instance, using counting blocks or colorful picture books will resonate more than abstract instructions. Furniture and materials should support role-playing, storytelling, and fine-motor exploration. Items like dramatic play centers, puppet theaters, and flexible seating arrangements are all ideal for this Piaget stage.

From a design and procurement perspective, this is also where the right preschool environment plays a transformational role. At this age, children benefit most from classrooms that allow movement, symbolic interaction, and imaginative storytelling. At XIHA Furniture, we recommend modular furniture pieces that promote role play, creativity, and group collaboration. Light wooden tables, bright visual dividers, and child-sized imaginative stations (like kitchens or doctor sets) are especially impactful.

More importantly, applying what we know about the Piaget stages of development ensures that environments foster growth rather than frustrate it. Children are not small adults—they are thinkers in progress. By respecting their stage-specific abilities, we nurture independent learners who grow with confidence.

Explore Piaget’s theory and egocentrism through SimplyPsychology

6. The Concrete Operational Stage: Logical Thinking (Ages 7 to 11)

The concrete operational stage is the third of the four Piaget stages of development, typically occurring between the ages of 7 and 11. At this point, children move beyond the symbolic thinking of the preoperational stage and begin to engage in more logical, organized, and rule-based thought—especially when dealing with tangible objects and real-world situations. This stage represents a crucial shift in the Piaget stages framework because children now begin to master concepts that involve logic and structure.

One of the key abilities that emerges in this Piaget stage is conservation—the understanding that quantity does not change even when its shape or appearance does. For instance, children learn that water poured into a taller, thinner glass still contains the same amount as when it was in a shorter, wider one. They also develop skills like classification (grouping objects by shared properties), seriation (ordering items along a quantitative dimension), and reversibility (understanding that actions can be undone).

These new cognitive abilities mark a significant milestone in the Piaget stages of development because they allow for better problem-solving, mathematical reasoning, and cause-and-effect analysis. Children in this Piaget stage also become less egocentric and more capable of considering multiple viewpoints, which helps them collaborate more effectively with peers.

From an educational perspective, this is the stage where educators can introduce structured activities like science experiments, math manipulatives, map reading, and storytelling with multiple plotlines. Learning becomes more systematic, and children thrive when information is presented in step-by-step formats. This is also the Piaget stage where students benefit most from group projects, hands-on learning stations, and task-specific classroom layouts.

The implications for learning environment design are equally important. Classrooms should be organized, clearly labeled, and equipped with visual guides that reinforce logical sequences. At XIHA Furniture, we recommend adjustable desks, labeled cubbies, math and science activity centers, and structured reading zones to match the cognitive strengths of this stage. Modular shelving, collaborative tables, and storage-friendly seating all support the concrete operational learner’s need for both structure and interaction.

Educators and curriculum planners should remember that although children in the concrete operational stage can think logically, their reasoning still depends on concrete references. Abstract concepts like algebra or hypothetical ethics will still be challenging. That’s why aligning classroom content and design with the characteristics of this Piaget stage leads to better educational outcomes and improved student confidence.

Understanding how the concrete operational stage fits within the broader Piaget stages of development allows teachers, parents, and decision-makers to optimize their approach. Children at this level are capable of amazing mental feats—if we create the right environment for them to explore.

7. The Formal Operational Stage: Abstract Reasoning (Ages 12 and Up)

The formal operational stage is the final and most advanced of the Piaget stages of development. Typically beginning around age 12 and continuing into adulthood, this stage marks a significant evolution in cognitive ability. Adolescents in this Piaget stage develop the capacity for abstract thinking, hypothetical reasoning, and deductive logic. Unlike earlier Piaget stages, thinking is no longer limited to concrete experiences—it expands to encompass ideas, symbols, and concepts that exist only in the mind.

A key milestone in the formal operational stage is the ability to think hypothetically. Students can now mentally test ideas without needing to manipulate physical objects. For example, they might consider ethical dilemmas, design science experiments, or explore philosophical questions. This level of reasoning makes it possible to grasp complex subjects like algebra, literary analysis, and scientific modeling—core academic skills that are vital in middle school and high school education.

In this Piaget stage of development, adolescents also begin to develop metacognition—the awareness of their own thought processes. They can analyze how they learn, question their own assumptions, and think about thinking. This skill is crucial for developing independent learners and critical thinkers.

Educators should take advantage of this newfound intellectual power by incorporating open-ended questions, debates, project-based learning, and theoretical challenges into their teaching methods. In the context of the Piaget stages of development, the formal operational learner thrives on challenge and autonomy. They appreciate opportunities to explore and justify multiple perspectives.

From an environmental design standpoint, classrooms for this Piaget stage should foster discussion, independent research, and creative exploration. At XIHA Furniture, we recommend ergonomic desks that support laptop use, flexible seating for group collaboration, and partitioned study areas for individual focus. Designated zones for project displays or science models also align with the abstract and self-directed nature of this Piaget stage.

It’s important to note that not all individuals reach this Piaget stage at the same time, or with the same depth of ability. Some students may still rely on concrete operational thinking in certain areas. This reinforces the importance of differentiated instruction, which allows students to engage with material in a way that matches their cognitive readiness across multiple Piaget stages.

By understanding the formal operational stage in the broader context of the Piaget stages of development, educators and school designers can better support adolescent learners as they transition into higher levels of abstraction, planning, and intellectual responsibility.

8. The Lasting Impact of Piaget’s Stages on Education

8.1 A Universal Framework for Education

The Piaget stages of development have left an indelible mark on educational theory and classroom practice worldwide. These stages are more than just abstract psychology—they are a framework for aligning curriculum, teaching strategies, and classroom design with how children actually think and grow. The influence of Piaget stages can be seen in everything from early childhood learning centers to modern high school science labs.

8.2 Stage-Specific Educational Design

Each of the Piaget stages plays a foundational role in shaping how educators structure learning. For instance, in the sensorimotor and preoperational Piaget stages, children need rich, hands-on experiences to explore their environment. This justifies the use of tactile materials, play-based learning, and activity zones tailored to their developmental stage. As children move into the concrete operational Piaget stage, they benefit from structured thinking, group interaction, and clearly defined academic goals. The final Piaget stage—the formal operational stage—encourages analytical thought, debate, and exploration of hypothetical ideas, all of which require a flexible and intellectually stimulating learning environment.

8.3 Curriculum Planning and Developmental Assessment

Educational psychologists and curriculum designers continue to rely on the Piaget stages as a tool for developmental assessment and pedagogical planning. These stages help identify not just what children are ready to learn, but how they are best able to absorb and apply knowledge. By respecting the boundaries and possibilities of each Piaget stage, educators avoid the pitfalls of mismatched expectations and frustration-driven learning blocks.

8.4 Classroom Environment and Furniture Innovation

Furniture and environment design are increasingly influenced by the structure of the Piaget stages of development. A classroom built with Piaget’s principles in mind will vary dramatically depending on the stage it serves. For example, a sensorimotor-friendly environment from XIHA Furniture includes soft, low-lying seating, tactile surfaces, and safe exploration spaces. A classroom designed for the concrete operational Piaget stage may include group workstations, labeled storage, and modular shelving for independent activity. In contrast, for students in the formal operational Piaget stage, we recommend ergonomic workspaces, flexible layouts, and areas for personal reflection and advanced research.

8.5 A Holistic Approach to Learning

When Piaget stages of development guide decisions in education, we build learning experiences that are empathetic, age-appropriate, and cognitively effective. This benefits not only academic success but also emotional development, peer cooperation, and student motivation. Whether you’re a preschool teacher, a school administrator, or a furniture supplier, understanding the Piaget stages is essential to your mission.

9. Benefits of Applying Piaget’s Theory in Early Childhood Settings

9.1 Smarter Classroom Design Based on Piaget Stages

Applying the Piaget stages of development in early childhood settings enables more intelligent classroom design. By aligning furniture, layout, and learning zones with specific cognitive abilities associated with each Piaget stage, we can create learning environments that support both independence and interaction. For instance, low open shelving, tactile mats, and sensory corners are perfect for sensorimotor learners. In contrast, symbolic learning corners and dramatic play setups suit children in the preoperational Piaget stage.

At XIHA Furniture, we’ve used insights from Piaget stages to design products that foster autonomy and exploration. When the physical environment reflects how children think, it encourages curiosity and reduces frustration—key goals for any preschool program.

9.2 Improved Teacher-Child Interaction

The Piaget stages of development inform educators about what kinds of interactions are most effective for children at different ages. A teacher working with preoperational children may use role play and storytelling to convey concepts, while a teacher working with concrete operational learners can focus on step-by-step reasoning and hands-on experiments.

When teachers know which Piaget stage their students are in, they can scaffold learning more effectively. This personalized approach leads to better engagement, improved learning outcomes, and stronger teacher-child bonds. It also supports emotional development, especially when instruction feels responsive to the child’s cognitive reality.

9.3 Parental Awareness of Developmental Milestones

Parents often worry whether their child is developing “on time.” The Piaget stages offer a research-based reference for tracking cognitive development. When early childhood educators communicate in terms of Piaget stages, parents gain insight into what skills their children are working on and why certain behaviors are expected.

Educators can use this framework to help parents understand everything from object permanence to logical operations. When families and schools speak the same developmental language, collaboration improves, and children benefit.

9.4 Enhanced Learning Through Age-Appropriate Play

One of the most powerful applications of the Piaget stages of development is in play-based learning. Each Piaget stage corresponds to different types of play. Sensorimotor learners explore textures and sound, preoperational children dive into symbolic play, concrete operational learners enjoy structured board games, and formal operational thinkers engage in strategic, rule-based challenges.

By intentionally designing play environments that reflect a child’s Piaget stage, educators can support learning that feels natural and joyful. This is especially effective in Montessori or Reggio Emilia-inspired settings, where materials are chosen to match developmental readiness.

10. Limitations and Challenges of Piaget’s Cognitive Stages

10.1 Not Every Child Follows the Same Timeline

One of the primary limitations of the Piaget stages of development is the assumption of universal age ranges. While Piaget proposed general timelines for each stage, in practice, children develop at different paces. Cultural background, learning environment, socio-emotional factors, and individual personality traits can all influence how and when a child progresses through the Piaget stages.

In early childhood education, relying too rigidly on these predefined stages could result in either overestimating or underestimating a child’s true abilities. Educators must balance Piaget’s framework with real-time observation and developmental assessments.

10.2 Underestimation of Children’s Abilities

Critics of the Piaget stages argue that Piaget may have underestimated children’s cognitive capacities, especially in the preoperational and concrete operational stages. Subsequent research has shown that, under the right circumstances and with appropriate guidance, many children can demonstrate more advanced thinking than Piaget’s framework might predict.

For example, with scaffolding and visual aids, some children as young as 4 can begin to grasp the concept of conservation—earlier than Piaget originally claimed. This suggests that while the Piaget stages of development provide valuable structure, they should not be used to limit expectations.

10.3 Cultural and Social Factors Are Overlooked

Another critique is that the Piaget stages focus primarily on individual cognition, with minimal emphasis on cultural, social, and linguistic factors that heavily influence learning. Vygotsky’s theory, for instance, addresses how social interaction and language play a central role in cognitive development—an area largely absent from Piaget’s original work.

Today, educators often combine insights from both Piaget and Vygotsky to design learning environments that consider both developmental stage and social context. This blended approach offers a more holistic understanding of how children learn.

10.4 Transition Between Stages Is Not Always Clear

While the Piaget stages describe clear boundaries between developmental phases, real-world transitions are rarely so tidy. Children may show traits of multiple stages at once or revert to earlier behaviors depending on the context. For example, a child might demonstrate formal operational reasoning during science class but rely on concrete logic in social situations.

Educators and designers must be flexible and responsive, recognizing that children exist along a continuum rather than in fixed cognitive boxes. This perspective allows for more personalized instruction, adaptable classroom setups, and better use of Piaget stages as a guide rather than a rulebook.

11. Practical Ways to Use Piaget’s Theory Today

11.1 Design Learning Spaces According to Piaget Stages

One of the most practical uses of the Piaget stages of development is in designing educational environments that correspond with children’s cognitive needs. Classrooms should reflect the thinking abilities associated with each Piaget stage. For example, early childhood classrooms serving the sensorimotor and preoperational stages should include interactive stations, open-ended play zones, and tactile sensory corners. Concrete operational learners benefit from clearly labeled storage, step-by-step visual guides, and logic-based task areas.

At XIHA Furniture, we design with these Piaget stages in mind. Our products for early learners support exploration and symbolic play, while our modular desks and activity units for older children foster collaboration and independent thinking. By structuring the space in a way that mirrors Piaget stages, learning becomes more intuitive, and transitions between activities feel more natural.

11.2 Choose Developmentally-Supportive Furniture

Furniture is a key factor in cognitive engagement. When chosen according to Piaget stages of development, classroom furniture becomes more than just a place to sit—it becomes a tool for learning. For sensorimotor learners, lightweight tables and movable seating promote gross motor exploration. In the preoperational stage, child-sized furniture with vivid colors supports symbolic thinking and self-expression.

As learners reach the concrete operational and formal operational Piaget stages, the need for flexible, ergonomic, and project-oriented furniture increases. At XIHA Furniture, we offer durable, adjustable options that adapt to evolving developmental demands, helping schools transition students seamlessly between stages.

11.3 Structure Lessons Around Stage-Based Thinking

Applying Piaget stages to lesson planning ensures that cognitive expectations match student readiness. Teachers can use the stages to guide how abstract or concrete a lesson should be. For example, in the preoperational Piaget stage, children benefit from storytelling, visuals, and hands-on materials. In the concrete operational stage, lessons that require organizing, sorting, or measuring are more effective.

Formal operational students can handle debates, abstract modeling, and theoretical discussions. By mapping instructional strategies to the Piaget stages of development, educators can better engage students at every age.

11.4 Foster Collaboration and Reflection

Each of the Piaget stages offers opportunities for social growth and metacognitive awareness. Educators can use group work and reflective activities to support these aspects of development. For example, concrete operational students enjoy collaborating on science experiments or building projects, while formal operational learners thrive in structured group debates or peer critiques.

Understanding how collaboration and self-reflection fit into the Piaget stages of development empowers educators to create more dynamic, student-centered classrooms. These practices not only promote learning but also build emotional intelligence, leadership skills, and academic confidence.

12. Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky: Two Cognitive Giants

12.1 Foundational Differences Between Piaget and Vygotsky

While both Piaget and Vygotsky made enormous contributions to developmental psychology, their theories differ significantly in approach. Piaget emphasized universal, biologically driven stages of development—known as the Piaget stages. He believed that children actively construct knowledge through independent exploration and interaction with the physical world.

In contrast, Vygotsky focused on the importance of culture, language, and social interaction in shaping cognitive development. He introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which refers to the difference between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance. Unlike the clearly defined Piaget stages, Vygotsky’s theory sees learning as a more fluid, socially mediated process.

12.2 Instructional Strategies: Piaget vs. Vygotsky

The Piaget stages suggest that educators should match instruction to a child’s developmental level. For example, a child in the concrete operational stage benefits from hands-on, logical tasks. Vygotsky, however, would encourage teachers to work just beyond a child’s current level, using scaffolding techniques to help them reach the next stage.

In practice, many educators blend both approaches. While the Piaget stages provide a reliable roadmap for understanding what children are ready to learn, Vygotsky’s ideas help guide how to teach it—particularly through dialogue, modeling, and social collaboration.

12.3 Implications for Classroom Design and Learning Environment

Designing spaces with Piaget stages in mind results in developmentally aligned environments. For example, preoperational learners thrive in classrooms with symbolic play zones, while formal operational learners benefit from abstract thinking spaces. Adding Vygotskian elements—such as peer learning stations and teacher-guided exploration areas—can enhance the cognitive richness of these environments.

🔍 Comparison Table: Piaget vs. Vygotsky

| Aspect | Piaget | Vygotsky |

|---|---|---|

| Focus of Theory | Cognitive development through biological maturation and active discovery | Cognitive development through social interaction and cultural tools |

| Key Concept | Piaget stages of development (sensorimotor → formal operational) | Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) |

| Role of Language | Language is a result of cognitive development | Language is central to cognitive development |

| Learning Process | Self-directed exploration and discovery | Learning is mediated through scaffolding and social interaction |

| Stages | Universal, sequential stages (4 stages) | No fixed stages; development is continuous and context-dependent |

| Role of Environment | Secondary to internal cognitive processes | Primary influence on cognitive growth |

| Role of the Teacher | Facilitator who sets up the environment for discovery | Guide or mentor who provides scaffolding in the ZPD |

| View on Egocentrism | Children are egocentric until they mature into perspective-taking | Egocentrism is reduced through dialogue and interaction |

| Application in Classrooms | Developmentally appropriate activities matched to Piaget stage | Group work, guided learning, peer collaboration |

At XIHA Furniture, we acknowledge the strengths of both theories. Our educational furniture is not only aligned with Piaget stages but also designed to support social interaction, peer learning, and teacher facilitation—bridging both perspectives in real-world educational settings.

13. Understanding Play in Cognitive Development

13.1 Play as a Cognitive Milestone in Piaget Stages

Play is more than entertainment—it’s an essential component of learning within the Piaget stages of development. Each stage corresponds to specific types of play that align with a child’s cognitive abilities. For example, in the sensorimotor Piaget stage, play involves sensory exploration—grasping, shaking, mouthing, and moving objects. This type of play builds foundational understanding of cause and effect.

During the preoperational stage, symbolic and pretend play become dominant. Children transform ordinary objects into imaginative tools—boxes become boats, and dolls become families. According to Piaget, this kind of play reflects growing symbolic function, a core element of the Piaget stages. Educators should recognize that supporting play is equivalent to supporting cognitive development.

13.2 Play Types Aligned with Each Piaget Stage

Understanding the progression of play helps early childhood professionals select materials and activities suited for each Piaget stage:

- Sensorimotor Stage: Rattles, textured mats, and water tables help children connect physical actions with outcomes.

- Preoperational Stage: Dress-up corners, puppet shows, and play kitchens promote symbolic reasoning.

- Concrete Operational Stage: Board games, puzzles, and STEM kits develop logic, sequencing, and planning.

- Formal Operational Stage: Strategic games, simulations, and design challenges foster abstract thinking and hypothesis testing.

Each category supports growth aligned with the corresponding Piaget stage. The role of the adult is to observe, scaffold, and adjust the environment to suit developmental needs.

13.3 Designing Play Spaces Based on Piaget Stages

Classroom and playground design should consider the needs of different Piaget stages. Younger children benefit from soft areas, sensory zones, and exploratory corners. As children enter later Piaget stages, the environment should evolve to include more structured, challenge-oriented areas.

At XIHA Furniture, we’ve developed a range of products to suit each stage. From modular soft-play systems for toddlers to logic and STEM-focused play stations for older students, our designs reflect the cognitive demands outlined in the Piaget stages of development. By integrating learning and play, we help schools foster creativity, independence, and holistic development.

14. Conclusion: Applying Piaget Stages in the Modern Learning Environment

The Piaget stages of development remain one of the most powerful tools available to educators, curriculum planners, and preschool designers. By understanding how cognitive abilities evolve across the sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational stages, we can design learning environments that truly support each child’s intellectual journey.

Throughout this guide, we’ve explored how the Piaget stages help shape everything from teaching methods and classroom design to parental engagement and child-centered play. These stages aren’t just theoretical—they offer a practical roadmap for making smarter educational choices every day.

At XIHA Furniture, we’ve fully embraced the principles of the Piaget stages of development in our product design and educational space planning. Whether it’s building flexible learning stations for concrete operational thinkers or symbolic play areas for preoperational learners, we are proud to support environments that grow with the child.

Incorporating the Piaget stages into early childhood practice doesn’t mean applying a rigid system. Rather, it means appreciating where each child is, responding to their cognitive needs, and preparing them thoughtfully for the stages ahead. It’s this mindset that builds not only better classrooms—but better learners.