In today’s fast-paced world, many parents worry about their children’s ability to concentrate and remember important information. With distractions everywhere—whether it’s digital devices, overstimulation, or even irregular routines—kids often struggle to focus during lessons and retain what they’ve learned. This challenge highlights the importance of supporting cognitive development, the process that strengthens memory, attention, and problem-solving.

Now, imagine a different scenario where your child can focus on tasks with ease, recall information quickly, and approach learning with curiosity and confidence. This is possible when parents and educators understand and support cognitive development—the natural process that strengthens a child’s memory, attention span, and problem-solving abilities. With the right guidance, kids not only perform better in academics but also develop life skills that set them up for future success.

In this article, we’ll explore how cognitive development directly impacts children’s memory and focus, why it matters in early development, and practical strategies you can use to support it every day. By the end, help your child build sharper thinking skills and a stronger foundation for lifelong learning.

Definition of Cognitive Development

Cognitive growth refers to the process by which individuals, especially children, develop their ability to think, learn, and understand the world. When parents or educators ask “what is cognitive development”, they are essentially inquiring about how the brain acquires knowledge, improves memory, sharpens focus, and develops problem-solving skills. Unlike physical growth that can be measured with height and weight, cognitive growth is more subtle and is observed through behaviors, reasoning, and learning milestones.

In simple terms, the cognitive growth definition can be described as the expansion of mental capacities that allow individuals to process information, reason logically, and build intellectual skills. To define cognitive development psychology, scholars point to the development of memory, attention span, decision-making, and creativity. It is a fundamental aspect of child development and continues throughout life, influencing how people adapt to challenges, learn new skills, and make sense of complex ideas.

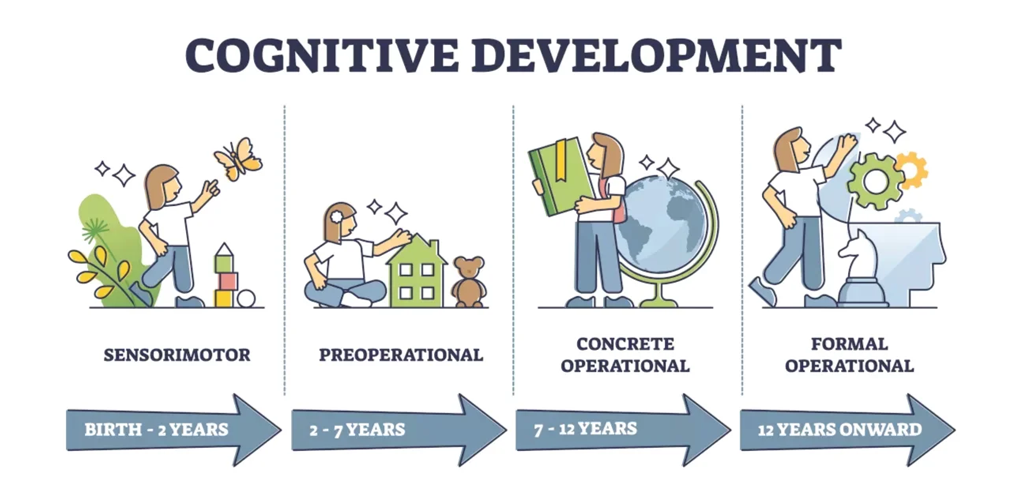

| Stage | Age | Thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor | Birth to 18-24 months | Object permanence |

| Preoperational | 2 to 7 years | Symbolic thought |

| Concrete operational | 7 to 11 years | Logical thought |

| Formal operational | Adolescence to adulthood | Scientific reasoning |

Why Cognitive Development Matters?

Cognitive growth is one of the most important areas of child development because it determines how children think, learn, and interact with the world. When we speak about cognitive and development, we are referring to the development of skills such as memory, focus, attention, and problem-solving. These abilities do not only affect academic performance but also influence how children communicate, manage challenges, and build confidence in daily life.

From a young age, cognitive growth shapes the way children approach learning. A child with well-developed cognitive skills can concentrate on lessons, remember instructions, and apply reasoning when solving problems. In contrast, children who experience delays in cognitive development may find it harder to keep up with schoolwork or adjust to new situations. This shows why parents and teachers should pay close attention to nurturing these abilities from the earliest stages.

Key Benefits of Cognitive Growth

- Improved Learning Outcomes: Children with stronger cognitive skills absorb and retain new knowledge more effectively.

- Better Focus and Memory: Cognitive growth supports longer attention spans and stronger recall abilities.

- Problem-Solving and Creativity: Kids develop the ability to think critically and find innovative solutions.

- Social and Emotional Growth: Reasoning skills improve communication, empathy, and collaboration with peers.

Beyond academics, it is also essential for lifelong success. Adults who continue to strengthen their cognitive abilities are better equipped to handle workplace demands, adapt to technology, and manage everyday challenges. In fact, studies show that investing in cognitive growth during early childhood leads to long-term benefits in academic achievement, career readiness, and emotional resilience.

Ultimately, From a young age, cognitive growth shapes the way children approach learning. A child with well-developed cognitive skills can concentrate on lessons, remember instructions, and apply reasoning when solving problems. In contrast, children who experience delays in cognitive development may find it harder to keep up with schoolwork or adjust to new situations. This shows why parents and teachers should pay close attention to nurturing these abilities from the earliest stages.

matters because it provides the foundation for continuous learning, adaptability, and personal development. By supporting it at home, in school, and across society, we give children—and future adults—the tools they need to thrive in an increasingly complex world.

History of Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

The history of Piaget‘s Theory of From a young age, cognitive growth shapes the way children approach learning. A child with well-developed cognitive skills can concentrate on lessons, remember instructions, and apply reasoning when solving problems. In contrast, children who experience delays in cognitive development may find it harder to keep up with schoolwork or adjust to new situations. This shows why parents and teachers should pay close attention to nurturing these abilities from the earliest stages.

begins in the early 20th century, when Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget first became interested in how children think and learn. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who believed that children were simply “miniature adults,” Piaget proposed that children pass through distinct stages of development, each characterized by unique ways of understanding the world. His work marked a turning point in psychology, education, and child development research.

Piaget’s interest in cognitive development started when he observed children’s mistakes during problem-solving tasks. He realized that their errors were not random but reflected systematic ways of thinking that changed as they grew older.

Impact on Education and Psychology

The significance of Piaget’s Theory of From a young age, cognitive growth shapes the way children approach learning. A child with well-developed cognitive skills can concentrate on lessons, remember instructions, and apply reasoning when solving problems. In contrast, children who experience delays in cognitive and development may find it harder to keep up with schoolwork or adjust to new situations. This shows why parents and teachers should pay close attention to nurturing these abilities from the earliest stages.

lies not only in describing these stages but also in showing that learning is an active process. According to Piaget, cognitive growth happens when children interact with their environment, test ideas, and adapt through processes of assimilation and accommodation. This perspective shifted education toward child-centered learning, encouraging teachers to create hands-on experiences that match students’ developmental levels.

Since its introduction, Piaget’s theory has influenced countless fields, from developmental psychology to pedagogy. While later scholars, such as Lev Vygotsky, expanded and critiqued Piaget’s framework, the historical importance of his theory remains undeniable. It established that cognitive development is not a passive accumulation of knowledge but a structured, stage-based process that continues to shape how researchers, teachers, and parents understand learning today.

Factors That Influence Cognitive Development

Cognitive development does not happen in isolation. It is shaped by a mix of biological, social, and environmental factors that interact to influence how children think, learn, and adapt to the world. Recognizing these influences helps parents and educators create the right conditions for healthy growth.

One of the strongest factors is biology. Brain maturation and genetics provide the foundation for memory, attention, and problem-solving. In the early years, neural connections are built at a rapid pace, making childhood a critical period for shaping long-term abilities. Any disruption, such as developmental delays or health conditions, can affect how quickly a child learns.

Nutrition and overall health also play a vital role. A balanced diet supports focus, concentration, and learning, while deficiencies can slow progress. Regular sleep and physical activity further strengthen brain function, giving children the energy and clarity they need to process new information.

The environment where a child grows up is another powerful influence. Homes and schools filled with books, conversations, and opportunities for play provide stimulation that fosters creativity and curiosity. Exposure to music, art, and problem-solving activities encourages abstract thinking and imagination, all of which support stronger learning outcomes.

Social relationships add another important layer. Interaction with parents, teachers, and peers helps children practice communication, reasoning, and collaboration. Supportive guidance builds confidence, while neglect or lack of stimulation can hold back progress.

In summary, the main influences include:

- Biological growth and brain development.

- Proper nutrition, sleep, and physical health.

- Stimulating environments with learning opportunities.

- Positive social and emotional relationships.

Together, these factors explain why Cognitive Development varies among children and why support must be comprehensive. By paying attention to biology, environment, and emotional security, parents and educators can give children the tools they need for stronger focus, better memory, and a love of learning that lasts a lifetime.

Understanding the Stages of Cognitive Development

Cognitive development theory is the gradual process through which children acquire the ability to think, reason, and solve problems. Jean Piaget’s theory remains one of the most influential frameworks for understanding how the mind evolves from infancy to adolescence. He proposed that children progress through distinct stages, each marked by unique ways of interacting with the world. These stages are not rigid, and individual differences, cultural influences, and learning environments can shape the pace of growth. Still, the model gives parents, teachers, and caregivers a roadmap to guide children effectively.

At its core, this journey is about moving from action-based learning in infancy to symbolic representation in early childhood, then to logical reasoning in middle childhood, and finally to abstract thought in adolescence. To understand why this matters, we will explore the four key stages of cognitive and development, their characteristics, and practical ways to support growth at each step.

The Sensorimotor Stage of Cognitive Development

This stage, from birth to two years, represents the foundation of all future learning. Infants rely on their senses and physical actions to understand their environment. Through trial and error, they begin to notice cause-and-effect relationships, laying the groundwork for memory and problem-solving.

Birth to 2 Years

Key developmental milestones include:

- Reflexes to Intentional Actions: Babies progress from simple reflexes to purposeful activities, like shaking a rattle to hear the sound.

- Object Permanence: Around 8–12 months, infants realize that objects continue to exist even when out of sight. Peekaboo is a classic example of this learning.

- Language Beginnings: Babbling leads to first words; shared attention and pointing accelerate vocabulary growth.

- Motor Exploration: Crawling, walking, and grasping objects expand opportunities to explore and learn.

Parents can support growth through sensory play, imitation games, and narrating daily activities. These interactions enhance attention, memory, and emotional bonding.

The Preoperational Stage of Cognitive Development

From ages two to seven, children enter a world of symbols and imagination. They can use words, drawings, and play to represent things, even when absent. Vocabulary expands rapidly, and storytelling becomes a favorite way to express ideas.

2 to 7 Years

Key features include:

- Symbolic Play: Pretend scenarios, like turning a box into a spaceship, help practice roles and problem-solving.

- Egocentrism: Children often assume others see the world as they do, making perspective-taking difficult.

- Centration: Focus on one feature at a time; for example, judging liquid by height rather than volume.

- Conservation Struggles: Difficulty understanding that quantity remains the same despite changes in appearance.

To guide development, adults can use storytelling, art, and role-play, while gently introducing logical reasoning. Visual aids like charts and number lines also help organize thinking.

The Concrete Operational Stage of Cognitive Development

From ages seven to eleven, children develop stronger logical skills but still depend on concrete, hands-on experiences. They understand rules, fairness, and can solve problems systematically when the material is visible or tangible.

7 to 11 Years

Key features include:

- Conservation Mastery: Children now recognize that amount remains constant despite changes in shape.

- Classification and Seriation: Ability to group objects by multiple features and arrange them in logical order.

- Reversibility: Understanding that actions can be undone, such as reversing math operations.

- Metacognition: Beginning to think about their own thinking processes, which supports planning and problem-solving.

Effective strategies include science experiments, real-world projects (like cooking), and group activities that encourage cooperation and fairness. Asking “How do you know?” helps children explain their reasoning and build confidence.

The Formal Operational Stage of Cognitive Development

Beginning around age twelve, children move into abstract thought. They can reason about hypothetical situations, test multiple variables, and analyze complex ideas. This stage extends into adulthood, with growth continuing through education and life experiences.

Age 12 and Up

Key features include:

- Abstract Reasoning: Ability to handle concepts like justice, morality, and hypothetical problems.

- Hypothetical-Deductive Thinking: Testing different solutions systematically to solve problems.

- Future Orientation: Planning long-term goals and imagining possibilities beyond current reality.

- Critical Thinking: Evaluating arguments, spotting fallacies, and weighing evidence.

Educators and parents can support development by offering open-ended projects, debates, coding or research challenges, and opportunities for self-reflection. Teaching how to analyze sources and construct arguments prepares adolescents for adult responsibilities.

Cognitive Development Examples

Understanding cognitive development in daily life helps bring the abstract principles of development cognitive theory into focus. Piaget, Vygotsky, and Bruner all emphasized that children’s thinking changes gradually through distinct stages, moving from concrete sensory experiences to complex abstract reasoning. These changes are not random but follow predictable patterns that can be seen in daily routines, classroom activities, and even playtime. By examining examples from early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence, we can see how theory translates into practice and how learning can be supported at every stage.

Early Childhood Examples: Learning Through Play

In early childhood, children are often in the preoperational stage of Piaget’s model. At this point, they rely heavily on imagination, symbolic representation, and play to make sense of the world. Development cognitive theory suggests that children construct knowledge actively, which explains why play-based activities are so powerful for growth.

Pretend play is one of the clearest examples: a cardboard box becomes a spaceship, or a doll takes on the role of a teacher. Through symbolic play, children practice social roles, problem-solving, and creative thinking. Storytelling and drawing also allow them to externalize their ideas, emotions, and experiences in ways that adults can observe.

Examples include:

- Language Expansion: Rapid vocabulary growth as children label objects, colors, and everyday routines.

- Egocentric Thinking: Assuming others see the same perspective, such as covering their eyes and believing they are invisible.

- Drawing and Storytelling: Expressing experiences through pictures and simple narratives.

- Role-Play Activities: Pretending to be a doctor, teacher, or firefighter, which builds empathy and imagination.

- Sorting Shapes and Colors: Engaging with blocks, puzzles, or Montessori materials to classify objects.

- Early Counting: Reciting numbers during play, even when sequencing is not fully accurate.

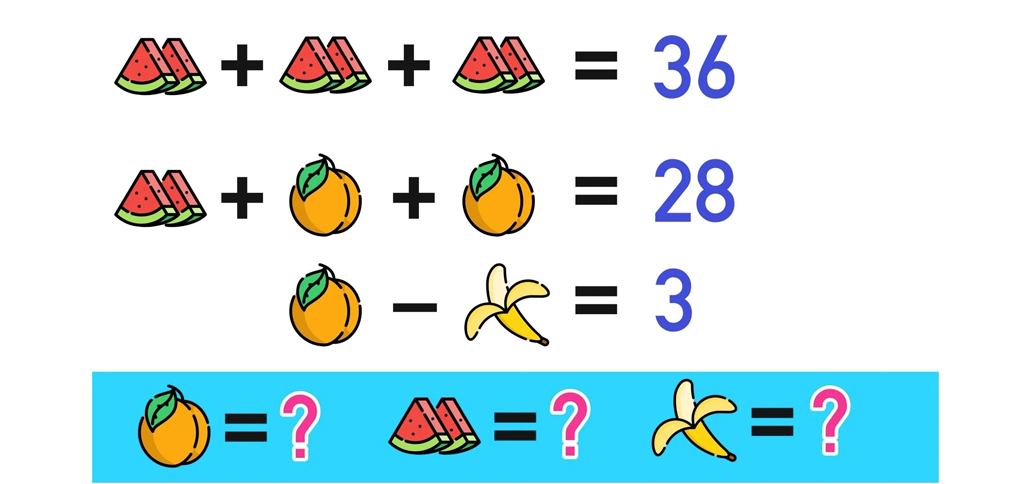

Middle Childhood Examples: Problem-Solving with Logic

From ages seven to eleven, children typically enter the concrete operational stage. According to development cognitive theory, this is when logical reasoning emerges, but thinking remains closely tied to concrete, hands-on experiences. Children begin to understand rules, fairness, and cause-and-effect relationships, which makes this stage particularly important for schooling.

In classrooms, children at this stage thrive when given opportunities to manipulate objects, test hypotheses, and see tangible outcomes. They can now recognize that appearances can be deceiving—for example, understanding that water poured into a tall, thin glass is the same volume as water in a short, wide one. Their ability to classify, order, and compare information grows rapidly, which is reflected in subjects like math, science, and even social studies.

Examples include:

- Conservation Tasks: Recognizing that quantity remains constant despite differences in appearance.

- Classification: Sorting objects by multiple attributes, such as size, shape, and category.

- Mathematical Reasoning: Using physical objects like blocks to solve addition or multiplication problems.

- Understanding Rules in Games: Learning to play board games fairly and respecting shared rules.

- Map Reading: Interpreting simple maps or diagrams to locate places and navigate.

- Cause-and-Effect Thinking: Predicting that planting seeds leads to plants, or understanding consequences in social situations.

These examples demonstrate why teachers often use manipulatives, science experiments, and collaborative group work at this stage. By engaging with concrete experiences, children strengthen logical reasoning while building confidence in their ability to solve problems systematically.

Adolescent Examples: Abstract and Hypothetical Thinking

By adolescence, children transition into the formal operational stage, where abstract and hypothetical reasoning become central. This stage, described extensively in development cognitive theory, is marked by the ability to think beyond the here and now. Teenagers can imagine multiple outcomes, test variables in experiments, and evaluate moral dilemmas with greater sophistication.

At this level, learning shifts from simple memorization to critical analysis. Teenagers begin questioning assumptions, debating social issues, and exploring identity. They can now think about thinking itself—a skill known as metacognition. This allows them to reflect on strategies for learning, evaluate arguments, and refine problem-solving techniques.

Examples include:

- Hypothetical Scenarios: Debating “what if” questions, such as solutions to global warming or futuristic technologies.

- Algebra and Advanced Math: Using variables and abstract equations beyond concrete numbers.

- Critical Thinking: Evaluating evidence, questioning sources, and identifying biases in arguments.

- Moral Reasoning: Reflecting on fairness, justice, and ethical dilemmas in literature or social debates.

- Future Planning: Setting long-term goals for education, careers, or personal growth.

- Scientific Experimentation: Designing controlled experiments to test hypotheses instead of relying only on observation.

These examples show how adolescents are preparing for adulthood. By combining abstract reasoning with metacognitive awareness, they can analyze complex issues and plan ahead. Educators at this stage should encourage open-ended projects, debates, and opportunities for critical inquiry to help students expand their intellectual capacity.

What is the Link Between Brain Growth and Cognitive Development?

The human brain is the central engine of learning, and its physical growth is closely tied to the process of cognitive development theory. As neural networks expand and strengthen, children gain new abilities in memory, reasoning, and problem-solving. The table below outlines the major connections between brain growth and cognitive milestones across development.

| Aspect of Brain Growth | Connection to Cognitive Development | Examples and Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Connections (Synaptogenesis) | Rapid growth of synapses in early childhood supports learning capacity. | Infants quickly pick up language sounds, object recognition, and cause-effect understanding through repeated experiences. |

| Pruning of Neural Pathways | The brain removes unused connections to become more efficient, shaping how children focus and think. | A child who practices math or music strengthens related pathways, while unused ones fade. This leads to specialization in skills. |

| Myelination (Faster Signal Transmission) | Coating of nerve fibers improves processing speed and attention span. | School-age children can solve problems more quickly, read fluently, and sustain concentration during lessons. |

| Prefrontal Cortex Growth | Supports executive functions like planning, impulse control, and decision-making. | Adolescents begin to think abstractly, evaluate consequences, and plan for the future. |

| Hippocampus Development | Critical for memory formation and retrieval. | Children improve in recalling instructions, stories, and academic content. Nutrition and sleep strongly influence this growth. |

| Plasticity (Adaptability of the Brain) | Allows the brain to reorganize itself in response to new experiences. | Bilingual children often show enhanced flexibility and problem-solving skills due to exposure to multiple languages. |

| Critical Periods of Growth | Certain skills are best learned during sensitive windows of brain development. | Early exposure to rich language environments supports stronger literacy and communication later in life. |

Applications to Education

Understanding cognitive development theory is not only useful for curriculum design but also for shaping the physical learning environment. The classroom setting, including the type of preschool furniture, plays a critical role in how children think, explore, and interact. When educational spaces are designed to support developmental needs, they become powerful tools for enhancing attention, problem-solving, and creativity.

Designing Stage-Appropriate Learning Environments

Just as lessons should match developmental stages, so should the classroom layout and materials. For preschoolers in the preoperational stage, child-sized tables, chairs, and storage units encourage independence and accessibility. Having furniture at the right height allows children to confidently manipulate objects, organize their supplies, and engage in pretend play without constant adult intervention. Flexible seating areas—such as floor cushions or low workstations—support exploration and movement, which are essential for early learning. Well-designed preschool furniture helps translate abstract concepts into hands-on experiences that children can physically interact with.

Supporting Active and Collaborative Learning

Active learning thrives when classrooms are equipped with versatile furniture. Movable tables, modular shelves, and lightweight chairs allow teachers to quickly reconfigure spaces for group work, storytelling circles, or individual projects. This flexibility supports the cognitive growth of preschoolers, who learn best through play, imitation, and collaboration. For example, arranging small groups around round tables fosters peer interaction, helping children practice perspective-taking and cooperative problem-solving. By using furniture as a tool for engagement, educators encourage both social and piaget’s theory of cognitive development in a natural, interactive way.

Encouraging Independence and Self-Regulation

Preschool years are also critical for building independence. Low open shelving units, labeled storage bins, and clearly defined learning stations give children control over their choices. This not only reinforces organizational skills but also develops metacognition—children learn to plan, select materials, and reflect on their work. Preschool furniture designed with accessibility in mind allows students to practice responsibility, such as cleaning up after activities or setting up their own workstations. These small acts of independence strengthen executive function skills like attention, memory, and self-regulation.

Integrating Social and Emotional Development

The physical classroom environment also influences social growth, which is tightly linked with cognitive progress. Group seating areas, dramatic play corners, and reading nooks encourage communication and empathy. Furniture that supports collaborative play, such as kitchen sets, puppet theaters, or role-play stations helps children navigate social rules while stimulating imagination. By creating inclusive spaces with developmentally appropriate furniture, teachers nurture both social-emotional learning and cognitive development, ensuring children feel confident, safe, and engaged. In addition, carefully designed preschool furniture provides opportunities for children to practice sharing, turn-taking, and negotiation—skills that form the foundation for healthy relationships. When these social experiences are combined with cognitive challenges, the result is a more balanced and holistic education.

Plowden Report

Age-Appropriate Learning

The report highlighted the importance of aligning educational content with children’s cognitive development. Drawing on Piaget’s theory, it stressed that learning activities should be designed to match a child’s stage of thinking and comprehension. By tailoring tasks to developmental readiness, educators can provide challenges that are stimulating without being overwhelming.

Concrete Experiences

In line with Piaget’s emphasis on hands-on exploration, the report underscored the value of concrete experiences in early learning. It recommended integrating practical activities, manipulatives, and real-life applications into classroom instruction. Such experiences help children connect abstract ideas to tangible examples, reinforcing understanding and memory.

Active Learning

The report also called for children to play an active role in their own education. Rather than simply absorbing information, learners should engage with their environment, test ideas, and build knowledge through discovery. This perspective reflects Piaget’s view that true cognitive development occurs when children construct meaning through interaction and participation.

“Children should be able to do their own experimenting and their own research. Teachers, of course, can guide them by providing appropriate materials, but the essential thing is that in order for a child to understand something, he must construct it himself, he must re-invent it. Every time we teach a child something, we keep him from inventing it himself. On the other hand that which we allow him to discover by himself will remain with him visibly”.

Piaget (1972, p. 27)

Help Kids Reach Cognitive Milestones

Children are constantly learning — not only at school but in every moment of daily life. As early childhood educators and suppliers of learning environments, we believe that supporting cognitive development goes far beyond textbooks and toys. It’s about creating a rich, supportive environment that invites curiosity, exploration, and growth. Here’s how we can help children hit those important cognitive milestones more effectively and naturally.

1. Cultivate Learning Experiences at Home

While educational institutions lay the foundation, it’s the home environment where much of a child’s early cognitive development takes shape. As such, parents, caregivers, and educators must work together to nurture environments filled with stimulating, developmentally appropriate experiences.

Set Up the Environment for Success

Children thrive when their learning spaces are predictable yet stimulating. A Montessori-inspired home environment, for example, encourages independence and hands-on engagement. Organizing furniture and materials at child height, incorporating natural materials, and rotating educational toys can keep the learning space fresh and interesting. We’ve seen that well-arranged learning corners—such as reading nooks, sensory stations, or science tables—can significantly impact a child’s ability to focus and absorb information. These simple setups create micro-environments of cognitive stimulation where children feel safe to explore and repeat actions.

Embed Learning in Daily Routines

Simple, daily interactions hold immense educational value. Measuring ingredients while baking, sorting laundry by color, or counting stairs when walking up can all be turned into cognitive learning moments. These activities encourage pattern recognition, sequencing, and logic—all foundational for advanced reasoning skills. Integrating language, numeracy, and memory games into everyday routines doesn’t require any special materials—just attentiveness and consistency from adults.

2. Encourage Children’s Interest in the World

Children are naturally curious. When nurtured correctly, this curiosity becomes the foundation of all future academic and social learning. Instead of steering children toward specific outcomes, we should provide them with the space and resources to explore topics and questions that excite them.

Support Open-Ended Play

Open-ended play materials like wooden blocks, animal figurines, or nature items help children explore cause and effect, build narrative thinking, and enhance creativity. These activities are not just about fun—they are rich in cognitive development. By resisting the urge to over-structure children’s playtime, we offer them room to practice problem-solving, experiment with storytelling, and explore self-regulation.

Connect to Real-World Topics

Children are deeply interested in what they see and experience. If a child sees snow for the first time, that moment can be expanded into lessons about temperature, geography, and even emotional responses.

We recommend having a shelf or learning board that rotates according to the child’s current interests—planets, insects, weather, or vehicles. This kind of responsive learning is foundational in both Montessori and Reggio Emilia philosophies and allows educators to build rich, meaningful lesson plans that align with each child’s individual pace and passion.

3. Demonstrate Information Effectively

Children absorb more when information is presented clearly, slowly, and meaningfully. Whether you are showing a child how to tie their shoes or explaining how plants grow, it’s not just the “what” but also the “how” that matters.

Use Modeling and Repetition

Young children are incredible mimics. They learn best when we model behavior or demonstrate a task clearly, then give them the chance to try it independently. This kind of scaffolding—first showing, then guiding, then stepping back—builds confidence and reinforces memory.

In a classroom, a teacher might slowly demonstrate pouring water from one jug to another. At home, a parent might show how to clean up toys one by one. Repeating these demonstrations over time helps reinforce neural pathways and builds cognitive fluency.

Break Down Complex Concepts

Chunking is an important cognitive technique for children. Breaking down a complex task into smaller steps allows them to digest information at their own pace. Visual cues, storyboards, and step-by-step instructions are tools that help scaffold complex learning.

4. Encourage Exploration

Cognitive development relies on a child’s freedom to explore and make mistakes. Exploration doesn’t just build knowledge; it strengthens memory, reasoning, and creative thinking.

Provide Safe Risk-Taking Opportunities

Climbing on a Montessori triangle ladder, building a tower, or even solving a puzzle that might be too hard—these are all forms of productive struggle. In early learning environments, it’s essential to offer challenges that are within reach but still require effort.

By supporting these challenges rather than solving them for the child, we allow them to build problem-solving skills and perseverance. These soft skills form the backbone of cognitive flexibility later in life.

Use Natural Materials and the Outdoors

Nature is one of the richest cognitive environments available to children. Observing bugs, following a trail of leaves, or feeling the texture of sand—these moments aren’t just physical play. They’re early science, early math, and emotional development all in one.

We’ve worked with hundreds of kindergartens to design indoor-outdoor learning environments that mimic nature’s rhythms. Children’s cognitive growth is accelerated when the learning extends beyond the classroom walls.

Can Piaget’s theory of cognitive development be applied to children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities?

Yes, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development can be applied to children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), but it must be approached with flexibility and individualization. Piaget outlined four key stages of cognitive development that children typically move through in sequence. However, children with SEND may progress at different rates, revisit earlier stages, or demonstrate abilities across multiple stages at once. What matters most is not strict adherence to the theory’s timeline, but understanding the core idea that children construct knowledge through experience. With thoughtful adaptation—such as more repetition, hands-on learning, visual cues, and sensory-friendly environments—educators and caregivers can support cognitive development in ways that honor each child’s unique strengths and needs. Rather than focusing on chronological age, it’s crucial to observe a child’s developmental readiness and design learning experiences accordingly. In doing so, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development becomes a helpful guide—not a limitation—in nurturing meaningful progress for children with SEND.

Conclusion

Helping children reach their cognitive milestones isn’t about accelerating development or turning every moment into a lesson—it’s about creating an environment rich in opportunity, curiosity, and connection. By cultivating meaningful learning experiences at home, encouraging children’s natural interests in the world, modeling thinking processes clearly, offering room for exploration, and asking thoughtful questions, adults become powerful partners in a child’s developmental journey. Each strategy—whether it’s narrating steps during a task, inviting curiosity during a walk, or demonstrating how to solve a problem—builds the brain’s ability to process, adapt, and reason.

Importantly, these practices align with proven cognitive development theories, including Piaget’s stages, and demonstrate how theory translates into everyday action. Whether you’re a parent, teacher, or caregiver, the goal is not perfection but presence—offering daily experiences that stretch thinking just enough to foster growth without frustration. In doing so, you not only support memory and focus but also lay the groundwork for lifelong learning, independence, and resilience.

FAQs

1. What are cognitive skills?

Cognitive skills are the core mental abilities the brain uses to think, learn, remember, reason, and pay attention. These skills include memory, attention, language, problem-solving, and logic. They are essential for acquiring knowledge and processing information. In early childhood, developing strong cognitive skills lays the foundation for academic learning, social interaction, and everyday decision-making.

2. What age is most important for cognitive development?

The most critical period for cognitive development is from birth to age 6. During this time, the brain is rapidly growing and forming connections in response to experiences. This window of development is when children absorb language, build memory, and begin problem-solving. High-quality learning environments and intentional play experiences during this stage have long-term impacts on a child’s ability to think and learn.

3. What age do cognitive issues start?

Cognitive issues can become noticeable as early as infancy or toddlerhood, especially if a child does not meet expected developmental milestones. For example, delayed speech, trouble focusing, or difficulties with memory may indicate an underlying cognitive delay. However, some cognitive challenges may only become clear when children begin school and face more structured learning demands. Early observation and assessment are key to timely support.

4. What are the 7 stages of brain development?

- Prenatal Stage (conception to birth)

- Infancy (birth to 2 years)

- Early Childhood (2 to 6 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 12 years)

- Adolescence (12 to 18 years)

- Early Adulthood (18 to 25 years)

- Mature Adulthood (25+ years)

5. Why do children need cognitive development?

Cognitive development equips children with the ability to understand the world, solve problems, make decisions, and learn from experiences. It impacts every aspect of life, from academic success to emotional regulation and social relationships. Supporting cognitive development helps children grow into independent thinkers and effective communicators.

6. What is cognitive thinking?

Cognitive thinking refers to the mental processes involved in acquiring knowledge and understanding. It includes attention, memory, logic, reasoning, and the ability to reflect and make judgments. In children, cognitive thinking begins with simple cause-and-effect understanding and gradually evolves into complex reasoning and abstract thought as they grow older.